History Writing Moves On

Abstract

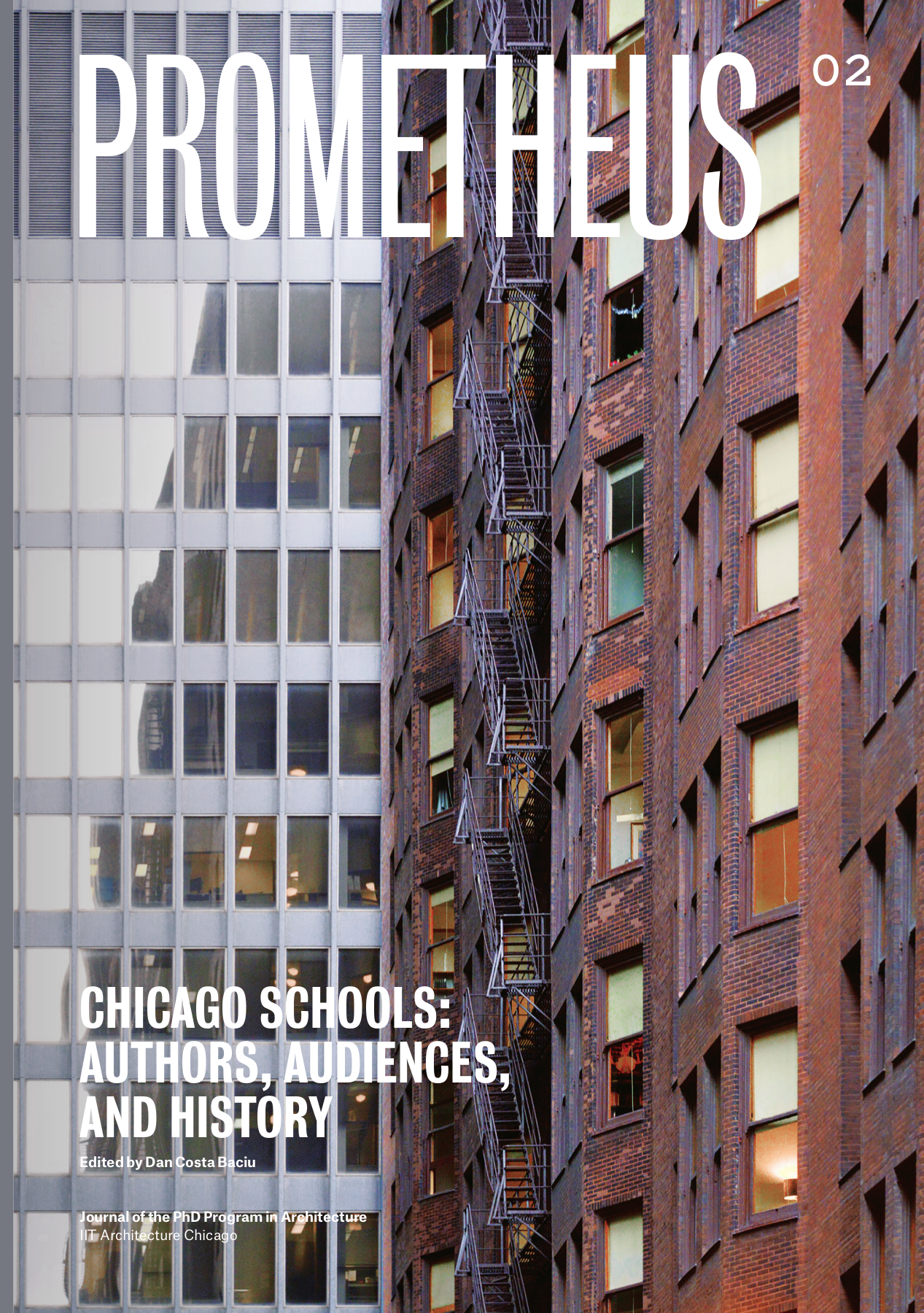

If a city can represent an idea, Chicago has long represented modernity. As the organizers of this symposium noted in the call for papers, beginning in the late-nineteenth century the city formed a nucleus for emerging modern theories across various disciplines, from architecture and psychology to sociology and economics. For many years, the value of the Chicago school of architecture was that of prescience: It was seen to foreshadow a universal modern condition yet to come, a modern way of building, working, and living to which all people and cultures would aspire. Since the 1960s, however, some historians have challenged the idea of modernity, minutely examining it for signs of instability, internal contradiction, and imminent failure.

In the field of architecture, ideas of stylistic evolution and artistic expression have been replaced with socio-economic determinism. Master figures and masterpieces have been supplemented by the “recovery” of figures and projects overlooked in the canon. The heroic view of modern technology has been reconsidered and replaced within emerging frameworks of capitalism and globalization. Ideas of functionalism were replaced with concepts of signification. In this process the agency of a largely unseen and partially cohesive collective has displaced the agency of the individual, the lone genius, in the process of architectural creation and production.

Yet in Chicago, with its highly developed economy of architectural tourism, the collective spirit and the mythology of the Chicago school of architecture lives on. As Roland Barthes observed, like other cultural mythologies, it has assumed a cultural role so powerful that it cannot be overcome. Perhaps we find it reassuring to think we can make sense of the complex social, technical, economic, and political forces that made up modernity when it is laid out before us in an understandable (and consumable) urban landscape? It is surely comforting to imagine that this landscape has a unified aesthetic, an observable style created by nameable authors, which we can claim as a major cultural achievement? It is precisely these assumptions, and the persistence of the myth of the Chicago school, that renders the work of the historian imperative. The papers presented in this symposium contribute to the ongoing work of understanding why the idea of the Chicago school continues to resonate. While acknowledging the centrality of the myth to the history of our discipline and to popular history, they challenge its homogeneity, stability, and continuity. In the process, new historiographical themes and systems of knowledge organization emerge, and new methods of working and areas of attention are revealed. Most of all, the practice of history writing moves on.